Firefly researchers (professionals and community scientists alike) often find themselves on a steep learning curve when gathering data on firefly species, especially when they are using methods that don’t involve collecting specimens. This post breaks down some of the ways to ensure that the data you are collecting is as useful as possible for species, with a focus on documenting flashing fireflies.

1. Document first, identify later!

It’s understandable to want to quickly put a name to the lightning bugs we see. But sometimes, jumping to identify a firefly can lead to less careful observation and documentation. Consider the difference between noting “big dipper flash pattern” and “half-second yellow flashes given low to the ground while the firefly dips and swoops upward, repeated about every five seconds.”

Use your precious time during firefly surveys to collect lots of evidence to analyze later.

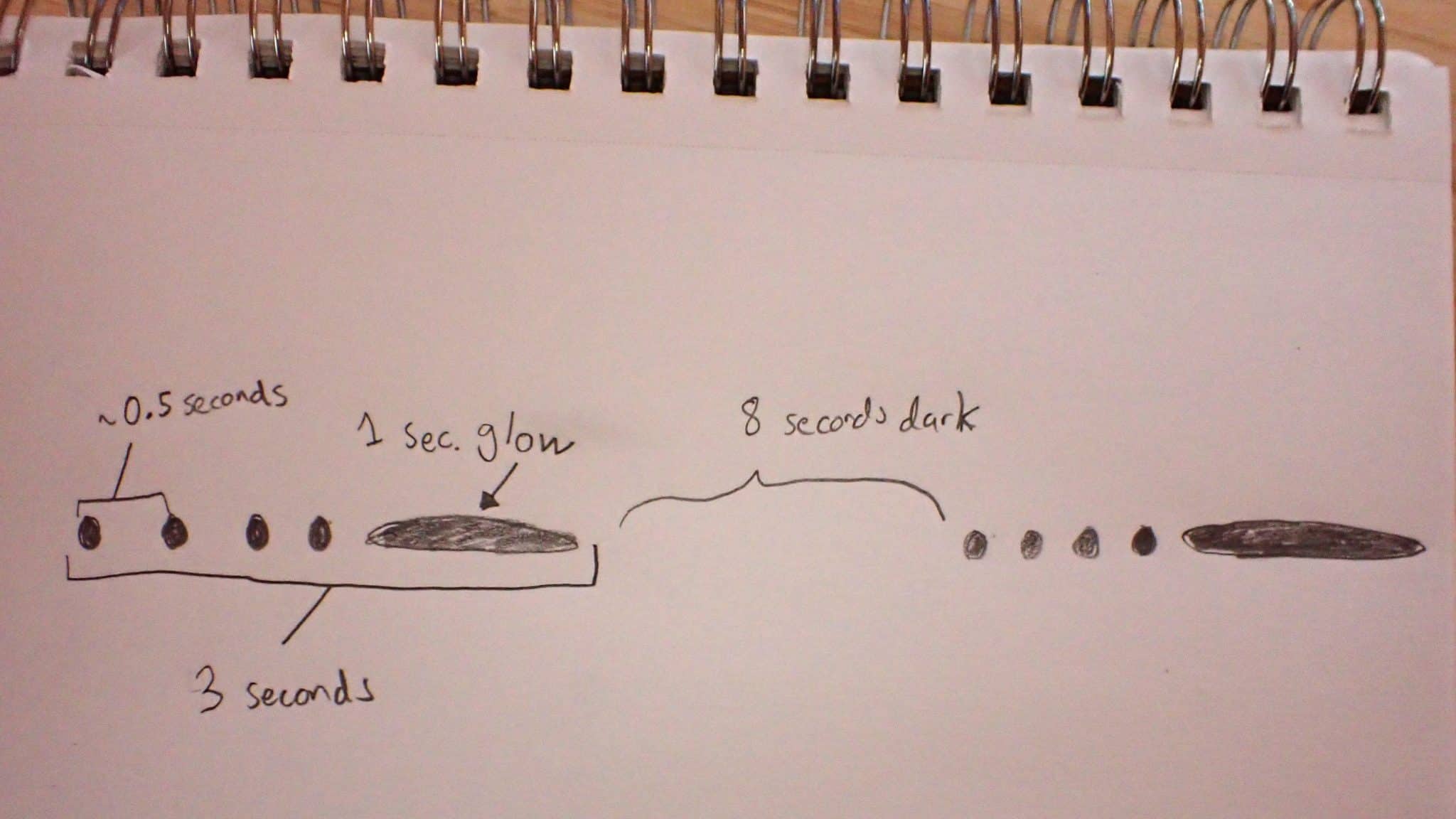

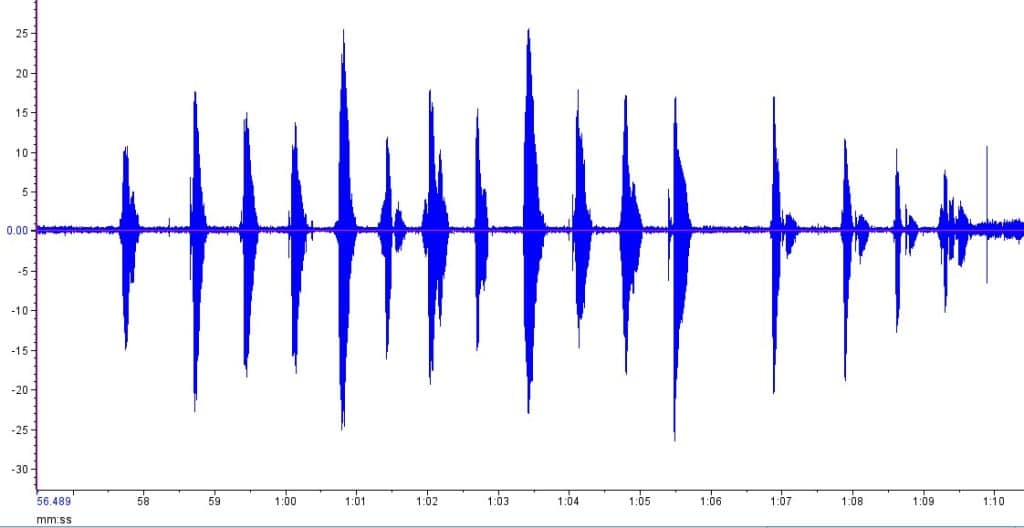

2. Sketch visual and verbal pictures of the firefly’s flashes through time

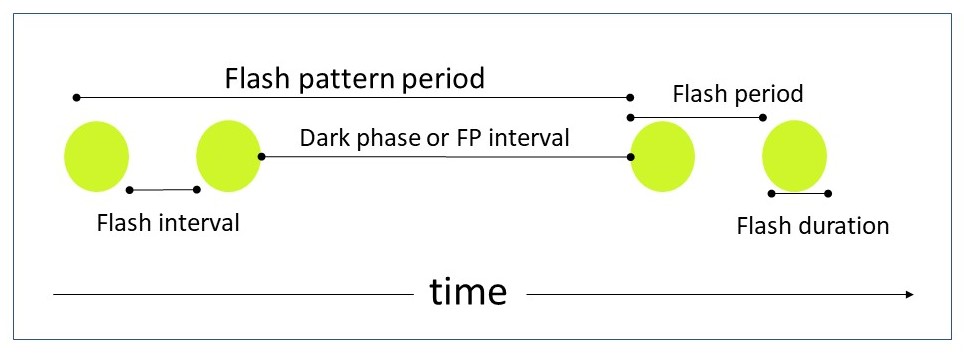

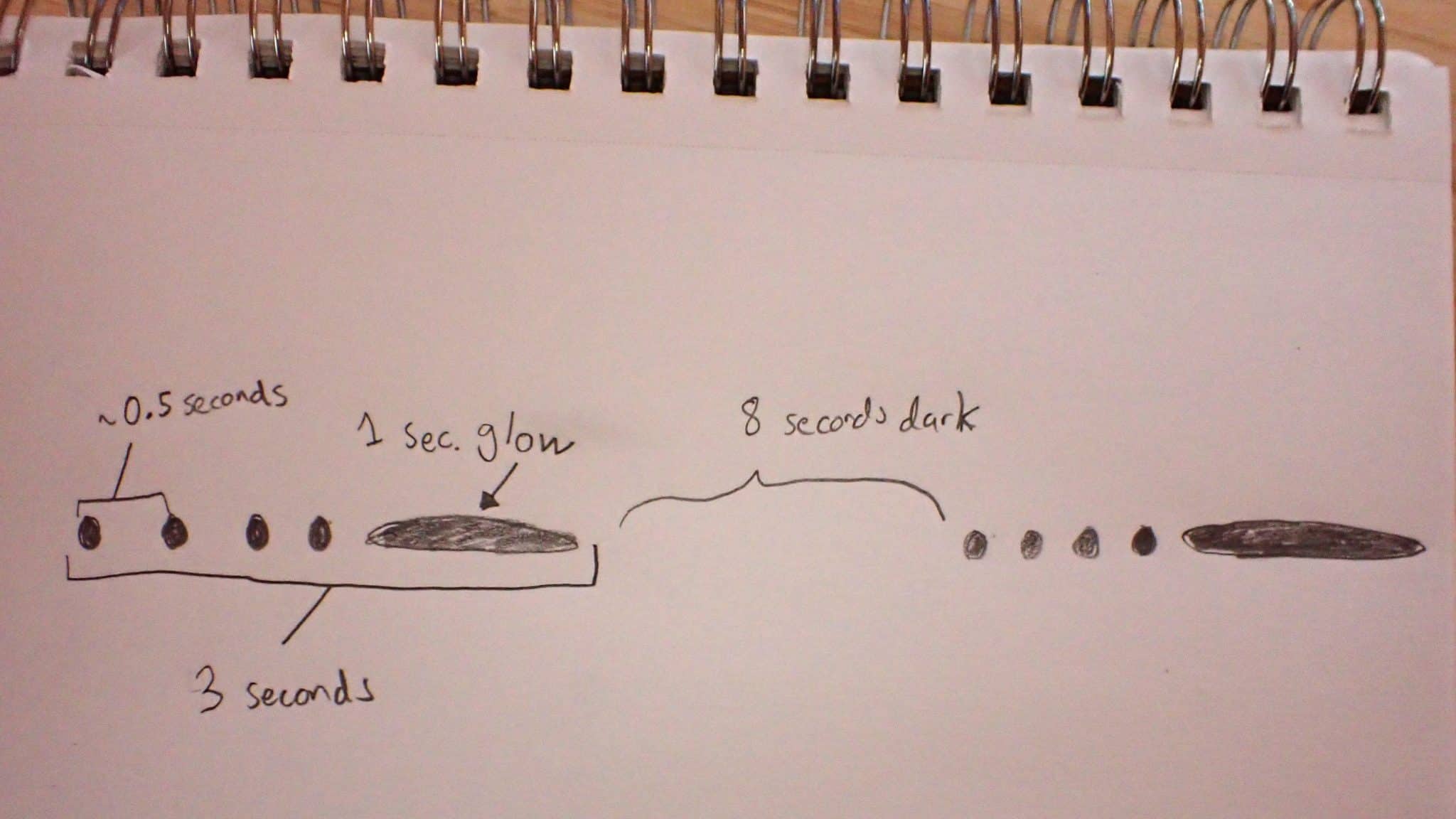

Imagine that the flashes in a firefly’s flash pattern are musical notes. What would it look like as sheet music? For decades, firefly researchers have used diagrams to illustrate the rhythm and parts of firefly flash patterns.

The timing of these flash patterns can then be characterized using standardized terms, such as those used on the Firefly Atlas data-sheet.

LINK: Flash pattern terminology

Complex flash patterns can also be described precisely using plain language. Here a few examples:

“The firefly’s flash pattern consists of sets of six quick, evenly-spaced pulses. Each set happens over about 1.5 seconds, and sets are repeated about every 10 seconds.”

“Flash pattern is two flashes, with 2 seconds between the flashes in each pair and pairs emitted every 6 seconds.”

It’s not just about measuring timing! Unleash your inner poet and describe the flashes. Are the flashes quick and “snappy”? Are they fast streaks? Hovering glows? Do they end abruptly like a flashbulb? Or do they slowly fade like a campfire ember? Is it a flicker (a string of quick flashes too quick to count)? These descriptions may seem subjective or fanciful, but when combined with timing measurement they can actually be quite helpful for identifying firefly species!

3. Capture flash patterns with your voice instead of video.*

Taking video on a smart phone can be a fun way to capture and share the experience of watching fireflies, and videos can sometimes be helpful for identifying species. But video isn’t always a practical way to document the flash pattern details needed for species identification. It’s often too hard to tell which flashes belong to which lightning bug, and the footage can be overwhelming and time-consuming to interpret.

Instead, by using a digital voice recorder (like the voice memo app on your phone), you can narrate the flashes of a single individual as it displays. Some fireflyers count out loud, while others simply make a sound (like a click) to represent each flash.

Here’s an example of me counting the flashes of an individual Florida single snappy firefly (Photuris congener)

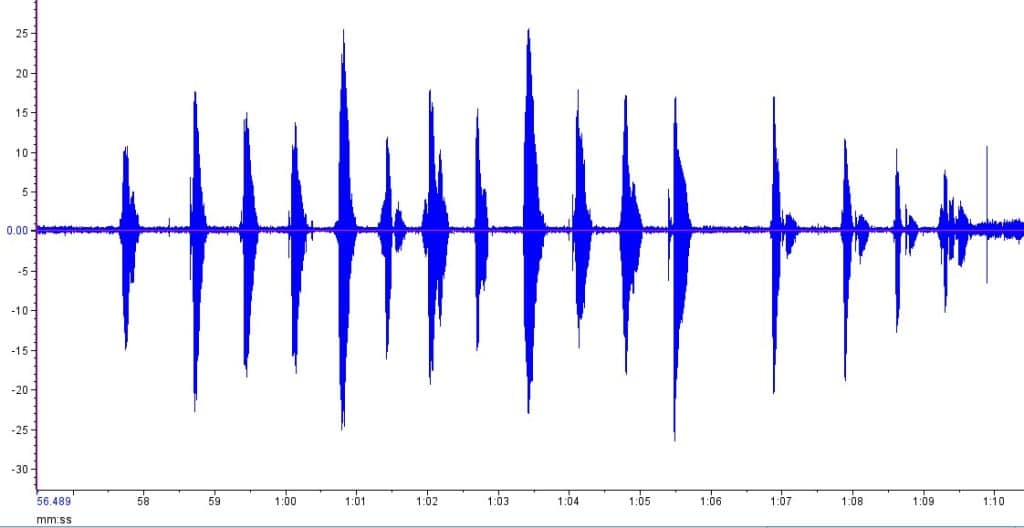

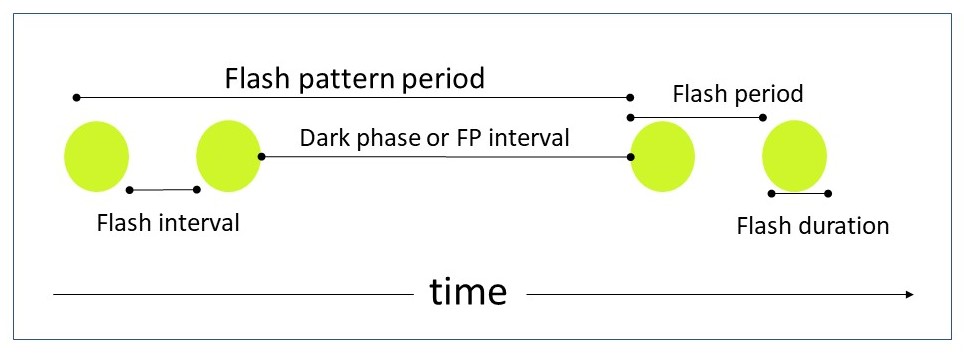

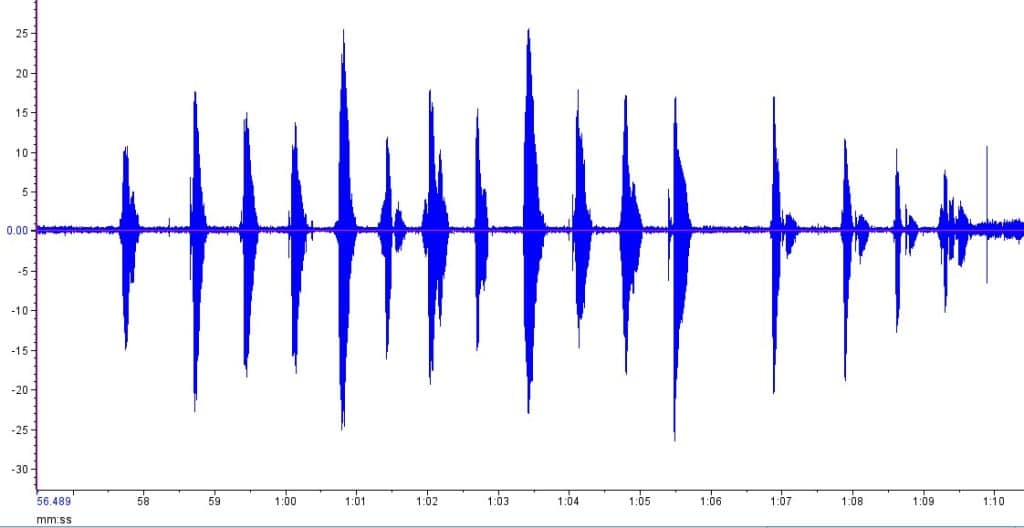

Once you are back from the field, you can use a stopwatch of the waveform function in audio software to measure the time between the flashes, which will show up as visual peaks. Below is a visual representation of the flash sequence created using a free bird song software program, showing that the flashes repeat about every 0.7 seconds.

LINK: Free bird song software program

*Researchers have successfully harnessed video recordings to study fireflies, but analysis of footage can be quite technical and computationally intensive.

4. Learn to tell male fireflies from female fireflies

It’s important to distinguish male fireflies from female fireflies because male flashes tend to be more useful for identifying species than female flashes.*

The sex of fireflies can be determined based on two things: what they look like and how they are behaving.

In fireflies that produce light as adults, females tend to have fewer light organs (lanterns) and these lanterns take up less space than they do on the male. Other differences include females having larger body sizes, bigger abdomens (more space for eggs), and smaller eyes.

Telling males from females based on behavior can be a bit trickier, depending on the species. However, if you see a firefly that is perched on the ground or on a leaf, and its flashes seem random or brief, there is a good chance it is a female. Fireflies that are flying and flashing in a predictable pattern, in contrast, are often males.

While it’s usually easier to identify males to species than females, you should pay attention to both. They are equally fascinating.

*Female flashes in Photinus do have value for species identification when seen as part of a flash-response dialogue between a male and a female. This takes very careful observation to document!

LINK: Flash-response dialogue between a male and a female

5. Get your camera close and fill the frame with the firefly.

This can be challenging if you are using a smartphone. To achieve, close-up, in-focus images, bring the camera up to the firefly slowly, hold the phone steady by using two hands or supporting the camera on a surface. There are relatively inexpensive macro lenses that can clip onto smartphone cameras, and many smartphones also have built-in macro settings.

If your photos have a lot of empty space around the firefly, cropping the photo before uploading to the Firefly Atlas will make it easier for reviewers to verify identifications.

6. When taking photo close-ups, use sandwich bags, not mayonnaise jars.

While many people have fond memories of putting fireflies in jars, it can actually be hard to get a good photo of a firefly inside a jar or vial. The curved surface can distort the image, and it is difficult to get the right angles and a sense of scale.

Instead, a small, clear plastic bag like a sandwich bag will let you gently hold the firefly still to get photos that show helpful traits and a sense of scale. Try to use bags that are clean and not too wrinkly or scratched.

In some cases, plastic petri dishes can be helpful for photographs as well, especially for fireflies that are sitting still rather than scrambling around.

7. Take a photo of the underside!

A view of the underside of a firefly gives you lots of information that you won’t get from the top side, and will really help you narrow down the possible species. This is another advantage of the plastic bag method (#6)—you can gently flip the bag over to see the underside of your firefly.

8. Show the size of your firefly (using the metric system).

We might think of all fireflies as being small, but in the US they can be as small as 5 millimeters or bigger than 20 millimeters. Photographing your firefly against a millimeter scale will often let you narrow down the list of possible species. If you have your Firefly Atlas data sheet with you, there’s a small scale already printed on the page that can be placed behind your firefly. Rite-in-the-rain field notebooks also often have built-in scales. Graph paper is another option—each grid square represents a specific measurement.

9. Remember to take an air temperature

The hotter it is, the faster fireflies flash, and if the temperature is too cold, fireflies won’t flash at all. Making a note of the air temperature is a key part of firefly data collection, because it helps us to calibrate our flash pattern observations and to better understand the range of temperatures at which a species is active.

You don’t need to buy fancy equipment to do this! An inexpensive cooking thermometer from the supermarket will likely be more accurate than using a weather app, especially if the nearest weather station is miles away.

10. Describe the firefly habitat.

It’s easy to focus entirely on the lightning bugs and their flashes, but collecting data on the habitats surveyed can teach us a lot about where fireflies thrive. Jot down a plant list (you can use iNaturalist or Seek for identification help), take notes about human activities on the landscape (mowing, for example), and include other habitat features like the water bodies.

By dialing in our understanding of what good habitat looks like for a given species, we better target for those species and we can also give more precise guidance to landowners who want to restore firefly populations.

Higher quality data means better-informed conservation

Having firefly data that is species-level and verifiable is vital for land managers, conservationists, and policy-makers. By applying these tips to your Firefly Atlas surveys and observations, you can light the way for fireflies to recover and thrive.

Notice: Below is a list of 4 important links included on this page.

3. Free bird song software program

4. Flash-response dialogue between a male and a female

Please note that while screen readers have made significant strides, they may still lack full support for optimal web accessibility.

Firefly researchers (professionals and community scientists alike) often find themselves on a steep learning curve when gathering data on firefly species, especially when they are using methods that don’t involve collecting specimens. This post breaks down some of the ways to ensure that the data you are collecting is as useful as possible for species, with a focus on documenting flashing fireflies.

1. Document first, identify later!

It’s understandable to want to quickly put a name to the lightning bugs we see. But sometimes, jumping to identify a firefly can lead to less careful observation and documentation. Consider the difference between noting “big dipper flash pattern” and “half-second yellow flashes given low to the ground while the firefly dips and swoops upward, repeated about every five seconds.”

Use your precious time during firefly surveys to collect lots of evidence to analyze later.

2. Sketch visual and verbal pictures of the firefly’s flashes through time

Imagine that the flashes in a firefly’s flash pattern are musical notes. What would it look like as sheet music? For decades, firefly researchers have used diagrams to illustrate the rhythm and parts of firefly flash patterns.

The timing of these flash patterns can then be characterized using standardized terms, such as those used on the Firefly Atlas data-sheet.

Complex flash patterns can also be described precisely using plain language. Here a few examples:

“The firefly’s flash pattern consists of sets of six quick, evenly-spaced pulses. Each set happens over about 1.5 seconds, and sets are repeated about every 10 seconds.”

“Flash pattern is two flashes, with 2 seconds between the flashes in each pair and pairs emitted every 6 seconds.”

It’s not just about measuring timing! Unleash your inner poet and describe the flashes. Are the flashes quick and “snappy”? Are they fast streaks? Hovering glows? Do they end abruptly like a flashbulb? Or do they slowly fade like a campfire ember? Is it a flicker (a string of quick flashes too quick to count)? These descriptions may seem subjective or fanciful, but when combined with timing measurement they can actually be quite helpful for identifying firefly species!

3. Capture flash patterns with your voice instead of video.*

Taking video on a smart phone can be a fun way to capture and share the experience of watching fireflies, and videos can sometimes be helpful for identifying species. But video isn’t always a practical way to document the flash pattern details needed for species identification. It’s often too hard to tell which flashes belong to which lightning bug, and the footage can be overwhelming and time-consuming to interpret.

Instead, by using a digital voice recorder (like the voice memo app on your phone), you can narrate the flashes of a single individual as it displays. Some fireflyers count out loud, while others simply make a sound (like a click) to represent each flash.

Here’s an example of me counting the flashes of an individual Florida single snappy firefly (Photuris congener)

Once you are back from the field, you can use a stopwatch of the waveform function in audio software to measure the time between the flashes, which will show up as visual peaks. Below is a visual representation of the flash sequence created using a free bird song software program, showing that the flashes repeat about every 0.7 seconds.

*Researchers have successfully harnessed video recordings to study fireflies, but analysis of footage can be quite technical and computationally intensive.

4. Learn to tell male fireflies from female fireflies

It’s important to distinguish male fireflies from female fireflies because male flashes tend to be more useful for identifying species than female flashes.*

The sex of fireflies can be determined based on two things: what they look like and how they are behaving.

In fireflies that produce light as adults, females tend to have fewer light organs (lanterns) and these lanterns take up less space than they do on the male. Other differences include females having larger body sizes, bigger abdomens (more space for eggs), and smaller eyes.

Telling males from females based on behavior can be a bit trickier, depending on the species. However, if you see a firefly that is perched on the ground or on a leaf, and its flashes seem random or brief, there is a good chance it is a female. Fireflies that are flying and flashing in a predictable pattern, in contrast, are often males.

While it’s usually easier to identify males to species than females, you should pay attention to both. They are equally fascinating.

*Female flashes in Photinus do have value for species identification when seen as part of a flash-response dialogue between a male and a female. This takes very careful observation to document!

5. Get your camera close and fill the frame with the firefly.

This can be challenging if you are using a smartphone. To achieve, close-up, in-focus images, bring the camera up to the firefly slowly, hold the phone steady by using two hands or supporting the camera on a surface. There are relatively inexpensive macro lenses that can clip onto smartphone cameras, and many smartphones also have built-in macro settings.

If your photos have a lot of empty space around the firefly, cropping the photo before uploading to the Firefly Atlas will make it easier for reviewers to verify identifications.

6. When taking photo close-ups, use sandwich bags, not mayonnaise jars.

While many people have fond memories of putting fireflies in jars, it can actually be hard to get a good photo of a firefly inside a jar or vial. The curved surface can distort the image, and it is difficult to get the right angles and a sense of scale.

Instead, a small, clear plastic bag like a sandwich bag will let you gently hold the firefly still to get photos that show helpful traits and a sense of scale. Try to use bags that are clean and not too wrinkly or scratched.

In some cases, plastic petri dishes can be helpful for photographs as well, especially for fireflies that are sitting still rather than scrambling around.

7. Take a photo of the underside!

A view of the underside of a firefly gives you lots of information that you won’t get from the top side, and will really help you narrow down the possible species. This is another advantage of the plastic bag method (#6)—you can gently flip the bag over to see the underside of your firefly.

8. Show the size of your firefly (using the metric system).

We might think of all fireflies as being small, but in the US they can be as small as 5 millimeters or bigger than 20 millimeters. Photographing your firefly against a millimeter scale will often let you narrow down the list of possible species. If you have your Firefly Atlas data sheet with you, there’s a small scale already printed on the page that can be placed behind your firefly. Rite-in-the-rain field notebooks also often have built-in scales. Graph paper is another option—each grid square represents a specific measurement.

9. Remember to take an air temperature

The hotter it is, the faster fireflies flash, and if the temperature is too cold, fireflies won’t flash at all. Making a note of the air temperature is a key part of firefly data collection, because it helps us to calibrate our flash pattern observations and to better understand the range of temperatures at which a species is active.

You don’t need to buy fancy equipment to do this! An inexpensive cooking thermometer from the supermarket will likely be more accurate than using a weather app, especially if the nearest weather station is miles away.

10. Describe the firefly habitat.

It’s easy to focus entirely on the lightning bugs and their flashes, but collecting data on the habitats surveyed can teach us a lot about where fireflies thrive. Jot down a plant list (you can use iNaturalist or Seek for identification help), take notes about human activities on the landscape (mowing, for example), and include other habitat features like the water bodies.

By dialing in our understanding of what good habitat looks like for a given species, we better target for those species and we can also give more precise guidance to landowners who want to restore firefly populations.

Higher quality data means better-informed conservation

Having firefly data that is species-level and verifiable is vital for land managers, conservationists, and policy-makers. By applying these tips to your Firefly Atlas surveys and observations, you can light the way for fireflies to recover and thrive.