Life Cycle

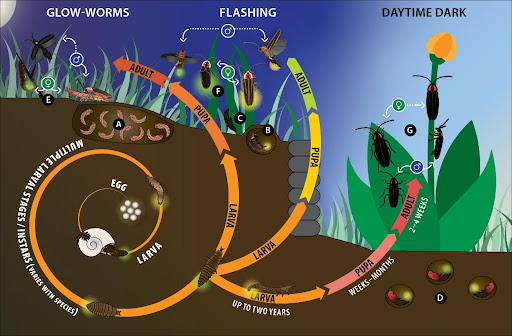

Fireflies—or lightningbugs—are not flies or bugs at all but are actually beetles in the family Lampyridae. Like all beetles, they undergo complete metamorphosis with four distinct stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult (Fig.1). The complete life cycle can take anywhere from a couple of months to two to three years or more, with the majority of the life cycle spent in the larval stage. Firefly larvae are voracious predators of soft-bodied invertebrates like snails, slugs, and worms. They typically hunt for their prey in moist soil or marshy areas, using their mandibles to inject them with paralyzing neurotoxins. Once their quarry is immobilized, they secrete digestive enzymes that liquefy the prey before consumption.

Figure 1: Fireflies spend most of their lives in the larval stage. After approximately two years as larvae, species pupate together (A) or alone (B) in shallow cavities at or slightly above soil level, aboveground on vegetation (C), or in shallow chambers an inch or two belowground (D). Flightless adult females (♀) are found in all three groups, varying from wingless (E) to different levels of short-winged (F), a.k.a. brachypterous, the most extreme of which are functionally wingless. While all three groups are bioluminescent as larvae and pupae, not all adults have functioning light organs, a.k.a. lanterns. Daytime dark fireflies and many adult male (♂) glow-worms do not produce light; in both groups the females may signal/attract males using light (glow-worms) or pheromones (G).

Bioluminescence

All Lampyrids create light using the same biochemical reaction, which takes place inside both larval and adult light organs, also known as lanterns. Although not all adults produce light, those that do can emit different colors (or wavelengths) of light varying from green to yellow to red. Firefly species active around twilight tend to emit yellower flashes, perhaps because they are easier to detect against the background of green light reflected off foliage, while those active in full darkness tend to emit greener flashes.

Adult courtship

Fireflies are best known for their bioluminescent courtship displays, yet while the larvae of all firefly species are bioluminescent, not all adults are capable of producing light. Fireflies thus fall into three main groups depending on their courtship style: daytime dark fireflies (Fig 2a), which are active during the day and do not produce light; glow-worm fireflies (Fig 2b), whose flightless females glow to attract mostly non-luminescent males; and flashing fireflies (a.k.a. lightningbugs, Fig 2c), which are probably our best-known fireflies due to the quick, bright flashes they produce.

Figure 2: Fireflies can be organized into three groups: daytime dark species (A), glow-worms (B), and flashing fireflies, or lightningbugs (C).

(Photo: Katja Schulz, Flickr)

(Photo: Ken-ichi Ueda, Flickr)

(Photo: Radim Schreiber)

Most of the flashing species in the US and Canada engage in flash dialogs during courtship. To attract the attention of females, flying males emit a particular flash pattern while patrolling an area. Females generally do not fly, but instead perch on low vegetation or on the ground. If a female is interested, she will respond to the male by flashing back. This flash dialog can continue for more than an hour until the male finally locates the female and they mate. Male flash patterns vary by species and may consist of single, double, or multiple pulses repeated at regular intervals. In Photinus fireflies, these flash patterns can be used to distinguish species. In Photuris fireflies, flash patterns are highly variable and individuals often emit different flash patterns depending on the time of night. Females of some Photuris species will also mimic the flash of other fireflies to lure them in for dinner.

In glow-worms, it is typically the females that glow to attract mostly non-luminescent males. Adult female glow-worms cannot fly, and their wingless bodies superficially resemble larvae rather than the typical adult body form. Adult males have evolved very large eyes in order to locate these rather sedentary glowing females. One exception to this pattern is the blue ghost firefly, Phausis reticulata, whose males emit long-lasting glows as they fly slowly over the forest floor, searching for dimly glowing females.

In addition to being active at different times of year, firefly species typically partition their courtship activity into different times of night. Some fireflies begin courting at dusk, and their courtship may last for just 20 minutes. Other species become active only when it is fully dark and may continue courtship for a few hours. Firefly flashing also depends on temperature, with faster flash rates and more activity occurring on warmer nights. Both the time of year and time of night that a species is active are helpful clues for identification.

Habitat associations

Fireflies are associated with a wide range of habitats, yet they all have one element in common—moisture. Fireflies have been documented in tidal marshes, desert river canyons, and cypress swamps, to name but a few (Fig 3). Some species are highly specialized, whereas others are generalists, occupying a range of damp meadows, forests, and marshes. Within these larger habitats, and depending on their life stage, fireflies require different microhabitats. Eggs and larvae may be found in moss, on the soil surface, under duff and leaf litter, or in rotting wood. Pupae can be found underground, in leaf litter, in small earthen chambers, or attached to herbaceous vegetation or in tree bark furrows. Flightless females do not stray far from their natal sites and may seek cover under leaves or twigs or in abandoned rodent burrows. Winged males and females may fly further afield and can be found throughout the canopy, in the understory, or on emergent vegetation. In the eastern US and Canada, fireflies may use ephemeral habitats such as irrigated lawns, agricultural fields, or damp meadows. In the West, fireflies are restricted to areas with permanent water sources, such as streams, rivers, lakes, and springs.

Figure 3: Fireflies can be found a diversity of habitats, from tidal marshes (A) to desert river canyons (B) and cypress swamps (C).

(Photo: Lee Cannon, Flickr)

(Photo: Sally Tudor, Flickr)

(Photo: Visit Mississippi, Flickr)