By Candace Fallon, Senior Endangered Species Conservation Biologist

I’ll cut straight to the chase: reality. Fireflies in the Pacific Northwest are very real, although they may not quite match up to the image you have in your mind.

Nineteen species of fireflies have been reported from the Pacific Northwest, which we are defining here to include Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and British Columbia. The catch is that most of these species do not flash, so they tend to fly (or crawl) under the radar. In this region, glow-worms and daytime dark (aka diurnal) species reign supreme, totaling seven and eight species, respectively. That leaves four species that flash. These flashing fireflies are rare and so far we know of populations only in Idaho and British Columbia. However, anecdotal reports abound in other areas of Washington and Oregon, and at least one published account indicates flashers are found in eastern Washington, suggesting that these bioluminescent beetles may be found in more places than is currently documented.

The western US firefly fauna is poorly known, especially compared to its more eastern counterparts. Over 50% (10 species total) of Pacific Northwest firefly species are considered Data Deficient (DD) on the IUCN Red List, meaning insufficient information is available to properly assess their conservation statuses. Eight species are categorized as Least Concern (LC), reflecting the fact that they are widespread and relatively common, and not expected to become extinct in the near future. One species has not been evaluated (NE), because the identity of this particular firefly is unclear. No fireflies in the Pacific Northwest are listed as threatened on the Red List, although researchers suspect some of the data deficient species will move to this category once more is learned about them.

LINK: IUCN Red List

To give you an idea of the diversity of fireflies in the Pacific Northwest, let’s take a little tour through the three different groups mentioned here, starting with the most species-rich group, the daytime dark fireflies.

Daytime dark fireflies

These fireflies—so named because they are active during the day and do not typically light up as adults—rely on chemical cues known as pheromones to find mates. However, their larvae are capable of producing light, which they use to deter predators. Daytime dark fireflies can be found in a variety of habitats, from wet westside forests to high desert riparian areas to coastal dunes, and are often encountered resting on vegetation. Although some species are known to congregate, most observations of are single individuals, making survey efforts for these species challenging. If you see a beetle out during the day that reminds you of a firefly, take a closer look. It could very well be a daytime dark species!

LINK: INaturalist

Eight species in two genera can be found in the Pacific Northwest (PNW), half of which are Data Deficient and the remaining of which are Least Concern. Until recently, all of the Photinus species listed here were grouped under the genus Ellychnia. Photinus is a large genus composed of both flashing and daytime dark firefly species. Some of these species have not been documented in the PNW in many decades, although this may reflect difficulties in identification, rather than true absence, especially since some specimens in museum collections and some photos on iNaturalist resemble these species. For example, the autumnal firefly (Photinus autumnalis) has not been recorded in over 70 years—the last official collection was in 1951. The granular-necked firefly was last officially seen in 1953. The obscured firefly, an Oregon endemic, is known only from type specimens collected in 1946.

Are these species still around, or have their populations all been extirpated? Are they simply overlooked, or mistakenly lumped with other more common species? Pacific Northwest Photinus are often lumped into Photinus corruscus and Photinus californicus, two potential species complexes that act as catch-alls for this confusing group of fireflies, particularly on platforms like iNaturalist. This can muddy the waters when trying to ascertain true species identifications and distributions, particularly since P. corruscus is thought to only occur in British Columbia, and P. californicus is largely confined to California, although it may stray into southern Oregon. Complicating matters further, the dichotomous keys used to differentiate the species are more than 50 years old and, while helpful, could use an update. There is clearly a need for more research on these poorly understood fireflies, including distribution surveys, taxonomic revisions, and life history studies.

| Species name | Recent synonyms | Common name(s) | Red List category | Adult activity period | Distribution |

| Photinus autumnalis | Ellychnia autumnalis | Autumnal firefly | DD | Mar – Apr | ID, WA, BC | AK, IN, MN, MT, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, RI, WI, AB, NT, ON, QC |

| Photinus corruscus | Ellychnia corrusca, Photinus corrusca | Winter firefly | LC | Feb – Jun | BC | AL, CO, CT, FL, GA, IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, MO, MT, NC, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NY, OH, PA, RI, TN, VA, VT, WI, WV, AB, MB, NB, NL, NS, NT, ON, QC, PE, YT, SK |

| Photinus faculus | Ellychnia facula, Photinus facula | Little torch firefly | DD | Mar – Sep | ID, OR, WA, BC | MT |

| Photinus fenderi | Ellychnia obscurevittata | Obscured-fillet firefly | DD | Jun | OR |

| Photinus granulicollis | Ellychnia granulicollis | Granular-necked firefly | DD | Aug | OR | MT |

| Photinus greeni | Ellychnia greeni | Green’s firefly | LC | Mar – Sep | OR, WA, BC | CA |

| Photinus hatchi | Ellychnia hatchi | Pacific Northwest firefly | LC | Apr – Oct | OR, WA, BC | CA, MT |

| Pyropyga nigricans | Black-bordered elf | LC | May – Sep | ID, WA, BC | AZ, CA, CO, IN, KY, ME, MI, MT, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OK, TX, UT, VA, AB, MB, ON, QC |

| Species name | Recent synonyms | Common name(s) | Red List category | Adult activity period | Distribution |

| Photinus autumnalis | Ellychnia autumnalis | Autumnal firefly | DD | Mar – Apr | ID, WA, BC | AK, IN, MN, MT, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, RI, WI, AB, NT, ON, QC |

| Photinus corruscus | Ellychnia corrusca, Photinus corrusca | Winter firefly | LC | Feb – Jun | BC | AL, CO, CT, FL, GA, IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, MO, MT, NC, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NY, OH, PA, RI, TN, VA, VT, WI, WV, AB, MB, NB, NL, NS, NT, ON, QC, PE, YT, SK |

| Photinus faculus | Ellychnia facula, Photinus facula | Little torch firefly | DD | Mar – Sep | ID, OR, WA, BC | MT |

| Photinus fenderi | Ellychnia obscurevittata | Obscured-fillet firefly | DD | Jun | OR |

| Photinus granulicollis | Ellychnia granulicollis | Granular-necked firefly | DD | Aug | OR | MT |

| Photinus greeni | Ellychnia greeni | Green’s firefly | LC | Mar – Sep | OR, WA, BC | CA |

| Photinus hatchi | Ellychnia hatchi | Pacific Northwest firefly | LC | Apr – Oct | OR, WA, BC | CA, MT |

| Pyropyga nigricans | Black-bordered elf | LC | May – Sep | ID, WA, BC | AZ, CA, CO, IN, KY, ME, MI, MT, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OK, TX, UT, VA, AB, MB, ON, QC |

Glow-worms

Next up we have the glow-worms. In this group, males fly and typically do not produce light as adults, whereas females are flightless and glow. Seven glow-worm species in three genera have been recorded from the Pacific Northwest, and all but two—the California pink glow-worm (Microphotus angustus) and the Douglas-fir glow-worm (Pterotus obscuripennis)—are Data Deficient. As their name suggests, California pink glow-worms are found predominantly in California, but at the northern extent of their range they can be found in southern Oregon. Flightless bubblegum pink adult females emit intermittent glows from the ground to attract males flying overhead. These females are frequently reported glowing from rocks and leaf litter in oak, chaparral, and pine woodlands. Another charismatic glow-worm, the Douglas-fir glow-worm, is rather common in Oregon, even appearing in urban parks like Portland’s Mt. Tabor and Powell Butte Nature Parks. Adult females of this species are white, soft-bodied ground dwellers, while adult males can sometimes be seen resting on vegetation during the day. The glowing larvae are large and grub-like, and can be found hunting in the leaf litter or in open grassy areas.

LINK: INaturalist

LINK: INaturalist

The Data Deficient Phausis glow-worms are another story altogether. Because males are small (typically 4-7 mm, depending on the species) and lantern-less, and females are likely sedentary and difficult to find, these species often get overlooked in survey efforts. Compounding this is the fact that none of the region’s Phausis larvae or adult females have been described (although you can see an unidentified Phausis larva here), so their behaviors and appearances are unknown. Their habitat associations are also largely undocumented, other than vague descriptions of adult males being found in forests. Much work remains to be done on the region’s Phausis glow-worm fauna.

LINK: Here

A variety of adult male glow-worms from the Pacific Northwest. From left: Phausis rhombica, P. riversi, P. skelleyi, and Pterotus obscuripennis. (Photos : left – Charlene Wood, BugGuide; two center – Joshua Dunlap, ODA; right – ozzimone, iNaturalist). Note the small, semi-transparent “windows” on the head shields of the Phausis species, and the feathery antennae of P. obscuripennis, which can be helpful for identification.

LINK: BugGuide

LINK: INaturalist

| Species name | Common name(s) | Red List category | Adult activity period | Distribution |

| Microphotus angustus | California pink glow-worm | LC | Apr – Jul | OR | CA |

| Phausis dorothae | Dorothy’s ghost | DD | Jun | OR | CA |

| Phausis nigra | Black ghost | DD | May – Jul | BC |

| Phausis rhombica | Rhombic ghost | DD | Jun – Jul | OR, WA, BC |AB |

| Phausis riversi | River’s ghost | DD | Jun – Jul | OR | CA |

| Phausis skelleyi | Skelley’s ghost | DD | Jun – Jul | OR, WA |

| Pterotus obscuripennis | Douglas fir glow-worm | LC | Mar – Jun | OR, WA | CA |

| Species name | Common name(s) | Red List category | Adult activity period | Distribution |

| Microphotus angustus | California pink glow-worm | LC | Apr – Jul | OR | CA |

| Phausis dorothae | Dorothy’s ghost | DD | Jun | OR | CA |

| Phausis nigra | Black ghost | DD | May – Jul | BC |

| Phausis rhombica | Rhombic ghost | DD | Jun – Jul | OR, WA, BC |AB |

| Phausis riversi | River’s ghost | DD | Jun – Jul | OR | CA |

| Phausis skelleyi | Skelley’s ghost | DD | Jun – Jul | OR, WA |

| Pterotus obscuripennis | Douglas fir glow-worm | LC | Mar – Jun | OR, WA | CA |

Flashing fireflies

Last but not least: the flashing fireflies. These are the fireflies people think of when they ask if fireflies occur in the Pacific Northwest. Four flashing species have been recorded from the region: the marsh flicker (Pyractomena dispersa), found in Idaho and potentially eastern Washington; the murky flash-train firefly (Photinus obscurellus), which occurs in British Columbia; an undescribed Photuris firefly, also from British Columbia; and possibly the big dipper firefly (Photinus pyralis) in southern Idaho.

The earliest of these species to emerge, the marsh flicker, is widespread across the country, but western populations are thought to represent an undescribed species. In the West, this firefly can be found in wet meadows, pastures, and fields at elevations up to 8,000 feet. It is active in the late spring through early summer, typically flashing just before sunset and continuing for an hour or two. It is Data Deficient but of conservation concern due to documented declines across its range. While eastern Washington populations have yet to be verified, numerous specimens from various parts of Idaho, including Bruneau, Hagerman, and Twin Falls, are housed at the William F. Barr Entomological Museum (University of Idaho) and Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History (The College of Idaho). At least one of these populations is thought to be extirpated.

Further north, in British Columbia, the murky flash-train firefly emerges in May or June from marshes and swampy areas near lakes. First flashes appear as darkness is descending, with the full show in swing by late evening. Another flashing firefly, previously identified as Photuris pennsylvanica, has also been recorded from the province, where it inhabits wetlands of the Rocky Mountain Trench in the east Kootenay region. However, recent taxonomic revisions have left this firefly without a species name, and it is unclear if populations still exist.

Photinus pyralis, the big dipper firefly, is arguably the most well-known firefly in the country. Found all across the eastern and central U.S., this species emerges at dusk on summer nights. There is just one mention of this species occurring in the Pacific Northwest: Kenneth Fender, who penned the firefly chapter in Hatch’s 1962 multi-volume book series The Beetles of the Pacific Northwest, included a description of Photinus pyralis from southern Idaho. However, no specimens were cited, and to date, we have not come across any museum records or published observations of this species in Idaho. Given high levels of search efforts for flashing fireflies in Utah, and no documented observations of this species along the northern Utah border, it remains to be seen if the big dipper actually occurs in this area.

| Species name | Common name(s) | Red List category | Adult activity period | Distribution |

| Photinus obscurellus | Murky flash-train firefly | LC | May – Aug | BC | CT, IL, IN, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, ND, NH, NJ, NY, OH, PA, SD, WI, WV, MB, NB, NL, NS, ON, QC, PE |

| Photinus pyralis | Big dipper firefly | LC | Jun – Aug | ID | AL, AR, CO, CT, DC, DE, FL, GA, IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, MD, MI, MN, MO, MS, NC, NE, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OK, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, VA, WI, WV, ON |

| Photuris sp. | Photuris firefly | NE | Jun – Jul | BC | MT? |

| Pyractomena dispersa | Marsh flicker; wiggle dancer (western states) | DD | Apr – Jun | ID, WA | AL, AR, AZ, CO, CT, DC, DE, GA, KY, MA, MD, ME, MI, MO, MS, NC, ND, NH, NJ, NV, NY, OH, OK, PA, TN, UT, VA, VT, WV, AB, MB, SK |

| Species name | Common name(s) | Red List category | Adult activity period | Distribution |

| Photinus obscurellus | Murky flash-train firefly | LC | May – Aug | BC | CT, IL, IN, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, ND, NH, NJ, NY, OH, PA, SD, WI, WV, MB, NB, NL, NS, ON, QC, PE |

| Photinus pyralis | Big dipper firefly | LC | Jun – Aug | ID | AL, AR, CO, CT, DC, DE, FL, GA, IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, MD, MI, MN, MO, MS, NC, NE, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OK, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, VA, WI, WV, ON |

| Photuris sp. | Photuris firefly | NE | Jun – Jul | BC | MT? |

| Pyractomena dispersa | Marsh flicker; wiggle dancer (western states) | DD | Apr – Jun | ID, WA | AL, AR, AZ, CO, CT, DC, DE, GA, KY, MA, MD, ME, MI, MO, MS, NC, ND, NH, NJ, NV, NY, OH, OK, PA, TN, UT, VA, VT, WV, AB, MB, SK |

So what about the rest of Washington, or even Oregon, for that matter? Fender specifically notes that luminescent fireflies are “confined to the region east of the Cascade Mountains, where they are rather rare.” Anecdotal reports of flashing fireflies have surfaced from both Oregon and Washington, although many of these originate from the 1950s and 60s. It is likely that some of these reports, particularly those from west of the Cascade Mountains, are erroneous. But what about the ones to the east? While some are questionable, others are a little more convincing. For example, in a 2016 Oregon Entomological Bulletin tribute to her father Bill Stephen, Beth Stephen Puton reminisces on summer evenings as a child when she and her siblings would catch fireflies at “an Experiment Station near Hermiston (eastern Oregon).” She notes that they spent four summers at this station. Were flashing fireflies once found in eastern Oregon and Washington, but have since been eradicated due to changing landscapes (e.g., agricultural development, loss of beaver wetlands), pesticide use, or changes in climate? Is it possible they still persist in small, isolated pockets?

LINK: Oregon Entomological Bulletin

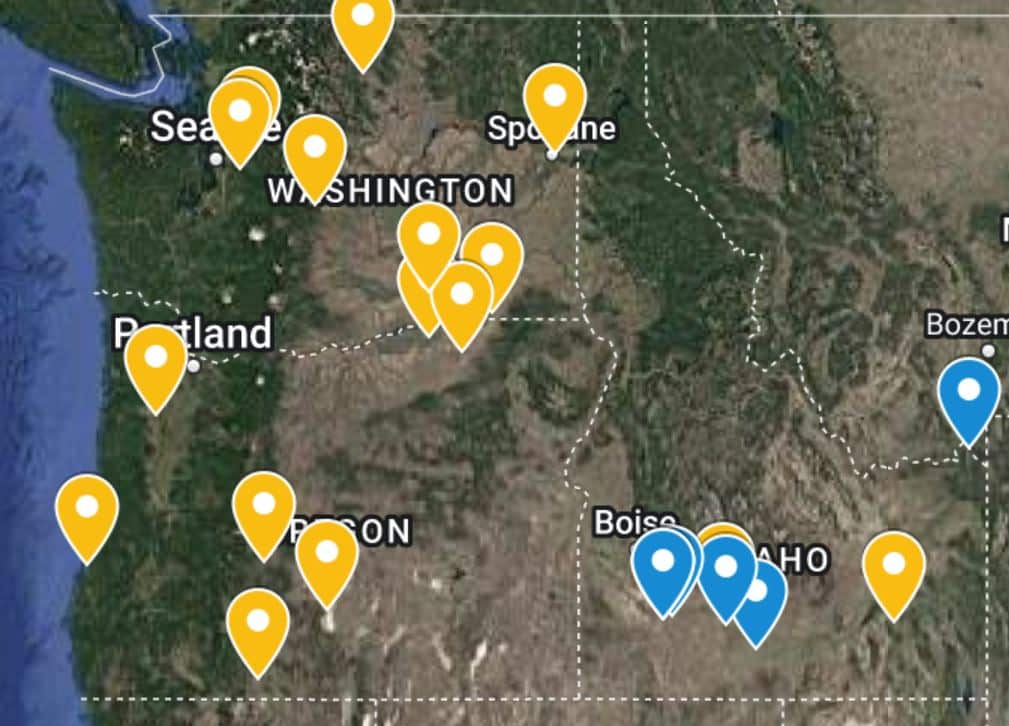

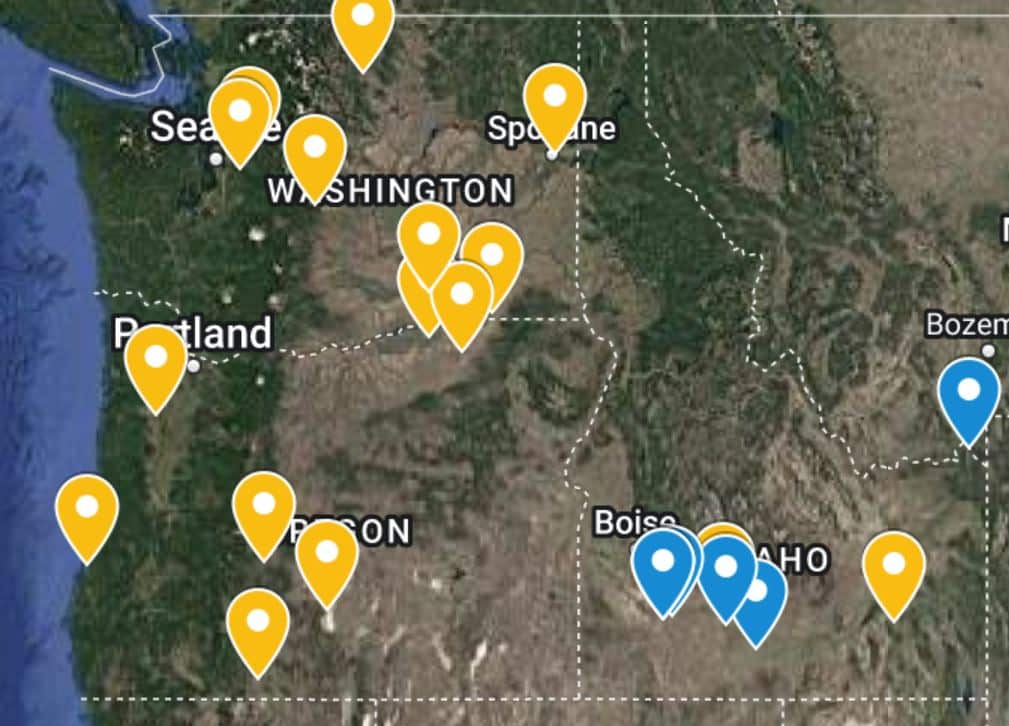

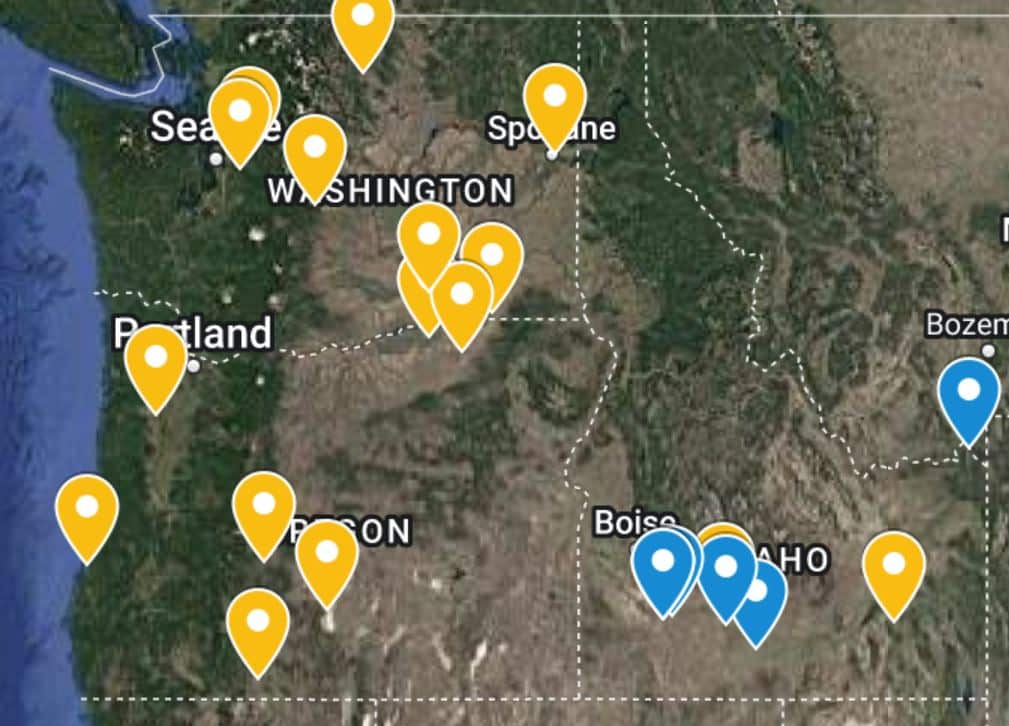

Pyractomena nr. dispersa fireflies like the one seen here have been documented from several locations in Idaho (blue points on map). But anecdotal reports of flashing fireflies have been emerged from across the PNW (yellow points on map). Is it possible there are (or were) populations of Pyractomena or other flashers in Oregon or Washington? (Photo: Robb Hannawacker, iNaturalist.)

LINK: INaturalist

Help us search for PNW fireflies!

There are a lot of unknowns when it comes to Pacific Northwest fireflies, including their distributions, habitat associations, female and larval morphology, behaviors, and life histories. Even though this region is not a focal area for the Firefly Atlas, your help is needed so researchers can get a better understanding of how the fireflies in this data deficient region are doing. We encourage you to pick a couple favorites this winter, identify some potential survey areas, grab a friend or two, and then head out and look for these species next spring and summer! With so many data gaps, there are a lot of opportunities for discovery, even in your own backyard or neighborhood park.

LINK: Focal area

PNW firefly references

Cannings, R.A., M.A. Branham, and R.H. McVickar. 2010. The fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) of British Columbia, with special emphasis on the light-flashing species and their distribution, status and biology. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 107:33-41.

Fender, K.M. 1962. Family Lampyridae. Pp. 34-43 In: M.H. Hatch. The Beetles of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Publications in Biology (16)3. Seattle, WA. 503 pp.

Fender, K.M. 1966. The genus Phausis in America north of Mexico (Coleoptera-Lampyridae). Northwest Science 40(3):83-95.

Fender, K.M. 1970. Ellychnia of western North America (Coleoptera: Lampyridae). Northwest Science 44: 31-43.

Notice: Below is a list of 10 important links included on this page.

2. INaturalist

3. INaturalist

4. INaturalist

5. Here

6. BugGuide

7. INaturalist

8. Oregon Entomological Bulletin

9. INaturalist

10. Focal area

Please note that while screen readers have made significant strides, they may still lack full support for optimal web accessibility.

By Candace Fallon, Senior Endangered Species Conservation Biologist

I’ll cut straight to the chase: reality. Fireflies in the Pacific Northwest are very real, although they may not quite match up to the image you have in your mind.

Nineteen species of fireflies have been reported from the Pacific Northwest, which we are defining here to include Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and British Columbia. The catch is that most of these species do not flash, so they tend to fly (or crawl) under the radar. In this region, glow-worms and daytime dark (aka diurnal) species reign supreme, totaling seven and eight species, respectively. That leaves four species that flash. These flashing fireflies are rare and so far we know of populations only in Idaho and British Columbia. However, anecdotal reports abound in other areas of Washington and Oregon, and at least one published account indicates flashers are found in eastern Washington, suggesting that these bioluminescent beetles may be found in more places than is currently documented.

The western US firefly fauna is poorly known, especially compared to its more eastern counterparts. Over 50% (10 species total) of Pacific Northwest firefly species are considered Data Deficient (DD) on the IUCN Red List, meaning insufficient information is available to properly assess their conservation statuses. Eight species are categorized as Least Concern (LC), reflecting the fact that they are widespread and relatively common, and not expected to become extinct in the near future. One species has not been evaluated (NE), because the identity of this particular firefly is unclear. No fireflies in the Pacific Northwest are listed as threatened on the Red List, although researchers suspect some of the data deficient species will move to this category once more is learned about them.

To give you an idea of the diversity of fireflies in the Pacific Northwest, let’s take a little tour through the three different groups mentioned here, starting with the most species-rich group, the daytime dark fireflies.

Daytime dark fireflies

These fireflies—so named because they are active during the day and do not typically light up as adults—rely on chemical cues known as pheromones to find mates. However, their larvae are capable of producing light, which they use to deter predators. Daytime dark fireflies can be found in a variety of habitats, from wet westside forests to high desert riparian areas to coastal dunes, and are often encountered resting on vegetation. Although some species are known to congregate, most observations of are single individuals, making survey efforts for these species challenging. If you see a beetle out during the day that reminds you of a firefly, take a closer look. It could very well be a daytime dark species!

Eight species in two genera can be found in the Pacific Northwest (PNW), half of which are Data Deficient and the remaining of which are Least Concern. Until recently, all of the Photinus species listed here were grouped under the genus Ellychnia. Photinus is a large genus composed of both flashing and daytime dark firefly species. Some of these species have not been documented in the PNW in many decades, although this may reflect difficulties in identification, rather than true absence, especially since some specimens in museum collections and some photos on iNaturalist resemble these species. For example, the autumnal firefly (Photinus autumnalis) has not been recorded in over 70 years—the last official collection was in 1951. The granular-necked firefly was last officially seen in 1953. The obscured firefly, an Oregon endemic, is known only from type specimens collected in 1946.

Are these species still around, or have their populations all been extirpated? Are they simply overlooked, or mistakenly lumped with other more common species? Pacific Northwest Photinus are often lumped into Photinus corruscus and Photinus californicus, two potential species complexes that act as catch-alls for this confusing group of fireflies, particularly on platforms like iNaturalist. This can muddy the waters when trying to ascertain true species identifications and distributions, particularly since P. corruscus is thought to only occur in British Columbia, and P. californicus is largely confined to California, although it may stray into southern Oregon. Complicating matters further, the dichotomous keys used to differentiate the species are more than 50 years old and, while helpful, could use an update. There is clearly a need for more research on these poorly understood fireflies, including distribution surveys, taxonomic revisions, and life history studies.

| Species name | Recent synonyms | Common name(s) | Red List category | Adult activity period | Distribution |

| Photinus autumnalis | Ellychnia autumnalis | Autumnal firefly | DD | Mar – Apr | ID, WA, BC | AK, IN, MN, MT, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, RI, WI, AB, NT, ON, QC |

| Photinus corruscus | Ellychnia corrusca, Photinus corrusca | Winter firefly | LC | Feb – Jun | BC | AL, CO, CT, FL, GA, IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, MO, MT, NC, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NY, OH, PA, RI, TN, VA, VT, WI, WV, AB, MB, NB, NL, NS, NT, ON, QC, PE, YT, SK |

| Photinus faculus | Ellychnia facula, Photinus facula | Little torch firefly | DD | Mar – Sep | ID, OR, WA, BC | MT |

| Photinus fenderi | Ellychnia obscurevittata | Obscured-fillet firefly | DD | Jun | OR |

| Photinus granulicollis | Ellychnia granulicollis | Granular-necked firefly | DD | Aug | OR | MT |

| Photinus greeni | Ellychnia greeni | Green’s firefly | LC | Mar – Sep | OR, WA, BC | CA |

| Photinus hatchi | Ellychnia hatchi | Pacific Northwest firefly | LC | Apr – Oct | OR, WA, BC | CA, MT |

| Pyropyga nigricans | Black-bordered elf | LC | May – Sep | ID, WA, BC | AZ, CA, CO, IN, KY, ME, MI, MT, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OK, TX, UT, VA, AB, MB, ON, QC |

Glow-worms

Next up we have the glow-worms. In this group, males fly and typically do not produce light as adults, whereas females are flightless and glow. Seven glow-worm species in three genera have been recorded from the Pacific Northwest, and all but two—the California pink glow-worm (Microphotus angustus) and the Douglas-fir glow-worm (Pterotus obscuripennis)—are Data Deficient. As their name suggests, California pink glow-worms are found predominantly in California, but at the northern extent of their range they can be found in southern Oregon. Flightless bubblegum pink adult females emit intermittent glows from the ground to attract males flying overhead. These females are frequently reported glowing from rocks and leaf litter in oak, chaparral, and pine woodlands. Another charismatic glow-worm, the Douglas-fir glow-worm, is rather common in Oregon, even appearing in urban parks like Portland’s Mt. Tabor and Powell Butte Nature Parks. Adult females of this species are white, soft-bodied ground dwellers, while adult males can sometimes be seen resting on vegetation during the day. The glowing larvae are large and grub-like, and can be found hunting in the leaf litter or in open grassy areas.

The Data Deficient Phausis glow-worms are another story altogether. Because males are small (typically 4-7 mm, depending on the species) and lantern-less, and females are likely sedentary and difficult to find, these species often get overlooked in survey efforts. Compounding this is the fact that none of the region’s Phausis larvae or adult females have been described (although you can see an unidentified Phausis larva here), so their behaviors and appearances are unknown. Their habitat associations are also largely undocumented, other than vague descriptions of adult males being found in forests. Much work remains to be done on the region’s Phausis glow-worm fauna.

A variety of adult male glow-worms from the Pacific Northwest. From left: Phausis rhombica, P. riversi, P. skelleyi, and Pterotus obscuripennis. (Photos : left – Charlene Wood, BugGuide; two center – Joshua Dunlap, ODA; right – ozzimone, iNaturalist). Note the small, semi-transparent “windows” on the head shields of the Phausis species, and the feathery antennae of P. obscuripennis, which can be helpful for identification.

| Species name | Common name(s) | Red List category | Adult activity period | Distribution |

| Microphotus angustus | California pink glow-worm | LC | Apr – Jul | OR | CA |

| Phausis dorothae | Dorothy’s ghost | DD | Jun | OR | CA |

| Phausis nigra | Black ghost | DD | May – Jul | BC |

| Phausis rhombica | Rhombic ghost | DD | Jun – Jul | OR, WA, BC |AB |

| Phausis riversi | River’s ghost | DD | Jun – Jul | OR | CA |

| Phausis skelleyi | Skelley’s ghost | DD | Jun – Jul | OR, WA |

| Pterotus obscuripennis | Douglas fir glow-worm | LC | Mar – Jun | OR, WA | CA |

Flashing fireflies

Last but not least: the flashing fireflies. These are the fireflies people think of when they ask if fireflies occur in the Pacific Northwest. Four flashing species have been recorded from the region: the marsh flicker (Pyractomena dispersa), found in Idaho and potentially eastern Washington; the murky flash-train firefly (Photinus obscurellus), which occurs in British Columbia; an undescribed Photuris firefly, also from British Columbia; and possibly the big dipper firefly (Photinus pyralis) in southern Idaho.

The earliest of these species to emerge, the marsh flicker, is widespread across the country, but western populations are thought to represent an undescribed species. In the West, this firefly can be found in wet meadows, pastures, and fields at elevations up to 8,000 feet. It is active in the late spring through early summer, typically flashing just before sunset and continuing for an hour or two. It is Data Deficient but of conservation concern due to documented declines across its range. While eastern Washington populations have yet to be verified, numerous specimens from various parts of Idaho, including Bruneau, Hagerman, and Twin Falls, are housed at the William F. Barr Entomological Museum (University of Idaho) and Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History (The College of Idaho). At least one of these populations is thought to be extirpated.

Further north, in British Columbia, the murky flash-train firefly emerges in May or June from marshes and swampy areas near lakes. First flashes appear as darkness is descending, with the full show in swing by late evening. Another flashing firefly, previously identified as Photuris pennsylvanica, has also been recorded from the province, where it inhabits wetlands of the Rocky Mountain Trench in the east Kootenay region. However, recent taxonomic revisions have left this firefly without a species name, and it is unclear if populations still exist.

Photinus pyralis, the big dipper firefly, is arguably the most well-known firefly in the country. Found all across the eastern and central U.S., this species emerges at dusk on summer nights. There is just one mention of this species occurring in the Pacific Northwest: Kenneth Fender, who penned the firefly chapter in Hatch’s 1962 multi-volume book series The Beetles of the Pacific Northwest, included a description of Photinus pyralis from southern Idaho. However, no specimens were cited, and to date, we have not come across any museum records or published observations of this species in Idaho. Given high levels of search efforts for flashing fireflies in Utah, and no documented observations of this species along the northern Utah border, it remains to be seen if the big dipper actually occurs in this area.

| Species name | Common name(s) | Red List category | Adult activity period | Distribution |

| Photinus obscurellus | Murky flash-train firefly | LC | May – Aug | BC | CT, IL, IN, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, ND, NH, NJ, NY, OH, PA, SD, WI, WV, MB, NB, NL, NS, ON, QC, PE |

| Photinus pyralis | Big dipper firefly | LC | Jun – Aug | ID | AL, AR, CO, CT, DC, DE, FL, GA, IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, MD, MI, MN, MO, MS, NC, NE, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OK, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, VA, WI, WV, ON |

| Photuris sp. | Photuris firefly | NE | Jun – Jul | BC | MT? |

| Pyractomena dispersa | Marsh flicker; wiggle dancer (western states) | DD | Apr – Jun | ID, WA | AL, AR, AZ, CO, CT, DC, DE, GA, KY, MA, MD, ME, MI, MO, MS, NC, ND, NH, NJ, NV, NY, OH, OK, PA, TN, UT, VA, VT, WV, AB, MB, SK |

So what about the rest of Washington, or even Oregon, for that matter? Fender specifically notes that luminescent fireflies are “confined to the region east of the Cascade Mountains, where they are rather rare.” Anecdotal reports of flashing fireflies have surfaced from both Oregon and Washington, although many of these originate from the 1950s and 60s. It is likely that some of these reports, particularly those from west of the Cascade Mountains, are erroneous. But what about the ones to the east? While some are questionable, others are a little more convincing. For example, in a 2016 Oregon Entomological Bulletin tribute to her father Bill Stephen, Beth Stephen Puton reminisces on summer evenings as a child when she and her siblings would catch fireflies at “an Experiment Station near Hermiston (eastern Oregon).” She notes that they spent four summers at this station. Were flashing fireflies once found in eastern Oregon and Washington, but have since been eradicated due to changing landscapes (e.g., agricultural development, loss of beaver wetlands), pesticide use, or changes in climate? Is it possible they still persist in small, isolated pockets?

Pyractomena nr. dispersa fireflies like the one seen here have been documented from several locations in Idaho (blue points on map). But anecdotal reports of flashing fireflies have been emerged from across the PNW (yellow points on map). Is it possible there are (or were) populations of Pyractomena or other flashers in Oregon or Washington? (Photo: Robb Hannawacker, iNaturalist.)

Help us search for PNW fireflies!

There are a lot of unknowns when it comes to Pacific Northwest fireflies, including their distributions, habitat associations, female and larval morphology, behaviors, and life histories. Even though this region is not a focal area for the Firefly Atlas, your help is needed so researchers can get a better understanding of how the fireflies in this data deficient region are doing. We encourage you to pick a couple favorites this winter, identify some potential survey areas, grab a friend or two, and then head out and look for these species next spring and summer! With so many data gaps, there are a lot of opportunities for discovery, even in your own backyard or neighborhood park.

PNW firefly references

Cannings, R.A., M.A. Branham, and R.H. McVickar. 2010. The fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) of British Columbia, with special emphasis on the light-flashing species and their distribution, status and biology. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 107:33-41.

Fender, K.M. 1962. Family Lampyridae. Pp. 34-43 In: M.H. Hatch. The Beetles of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Publications in Biology (16)3. Seattle, WA. 503 pp.

Fender, K.M. 1966. The genus Phausis in America north of Mexico (Coleoptera-Lampyridae). Northwest Science 40(3):83-95.

Fender, K.M. 1970. Ellychnia of western North America (Coleoptera: Lampyridae). Northwest Science 44: 31-43.