By Richard Joyce, Endangered Species Conservation Biologist

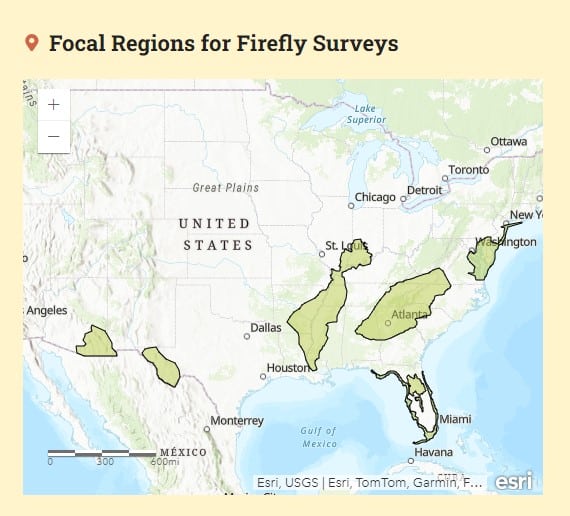

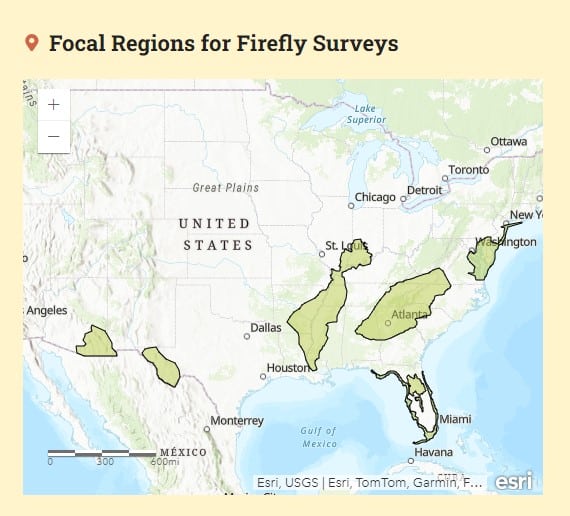

You’ve created a Firefly Atlas account, looked over the participant handbook, and watched the training video. You’ve read the Community Science Code of Conduct, gathered the equipment you’ll need, and printed out survey data-sheets. There’s just one issue: you don’t live in any of the focal regions highlighted on the map below.

LINK: Participant handbook

LINK: Training video

LINK: Community Science Code of Conduct

LINK: Survey data-sheets

The regions on this map correspond to areas with potential habitat for firefly species that are of particular concern for conservation in the United States, so Firefly Atlas participation in these regions is particularly valuable. However, firefly surveys from all across the USA and Canada are meaningful contributions to firefly conservation. Your geographic location will influence how you contribute to the Firefly Atlas, but it should not determine whether you participate.

In this blog post, I’ll explain how to direct your firefly survey efforts for the greatest contribution to firefly conservation, even if you live outside of a focal survey region.

Figure out which Data Deficient species could be in your area and then search for them.

Back in 2021 when the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Firefly Specialist Group carried out extinction risk assessments for the majority of North American firefly species, it was revealed that over half of the assessed species lacked the necessary information to determine their conservation status. In other words, these species could be doing fine (Red List Least Concern) or they could be in trouble (Red List Endangered), but we simply don’t know enough about their current distribution or population levels. The technical term for this category is “Data Deficient” (DD).

LINK: Carried out extinction risk assessments for the majority of North American firefly species

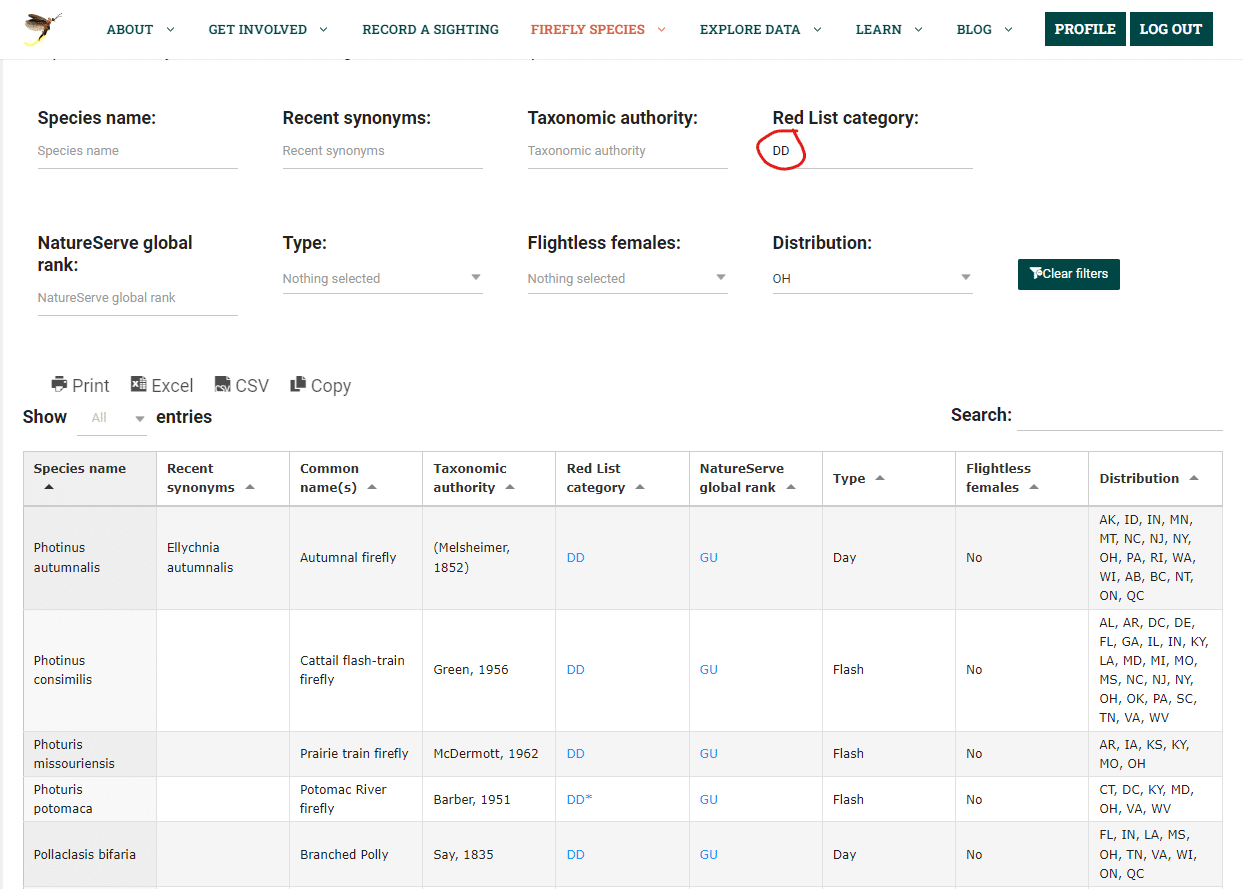

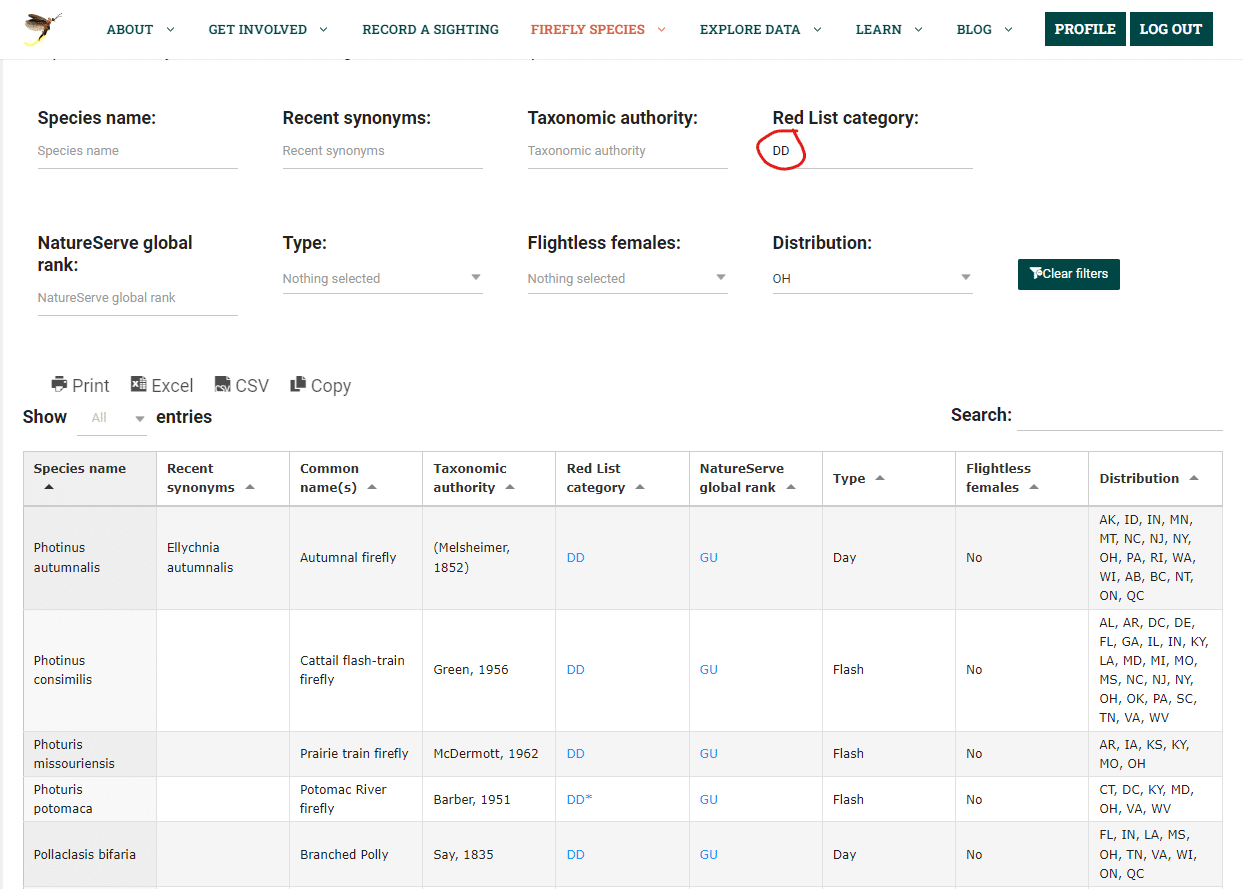

Using the Firefly Species Checklist, you can to filter species that have a Red List category of “DD” and are found in your state or province or in neighboring states and provinces.

LINK: Firefly Species Checklist

Here are some of the Data Deficient species for which Firefly Atlas participants have surveyed so far:

Once you’ve created a list of Data Deficient species that might be in your area, you can learn more about each of these species on their Red List pages, as well as in the available field guides, keys, and identification resources. These sources will help guide you on what time of year to survey, what flash patterns or other behavior to look for, and what habitats to survey in.

LINK: Available field guides, keys, and identification resources

Do a full inventory of firefly species for your local park or green space.

Another approach is to begin creating a full species list for whatever green space you have access to, whether that is your backyard or a local park or nature center. You can begin by documenting the most common species, and as you spend more time surveying for fireflies, you will likely start to notice fireflies that are less common.

Across North America, volunteer naturalists are making illuminating discoveries as they gradually create lists of the fireflies found in their local green spaces. For example, the “Glow Patrol Firefly Research Team” has successfully documented seven species at Armand Bayou Nature Center in Pasadena, Texas, and the volunteers at the firefly sanctuary at the Coler Mountain Bike Preserve in Bentonville, Arkansas are also inventorying their lightning bugs.

LINK: Armand Bayou Nature Center

LINK: Firefly sanctuary at the Coler Mountain Bike Preserve

Survey lots of sites for one species

Once you’ve found a given species and know that its display season has begun, you can explore the question of how widespread it is in your community. For example, you might collaborate with your local Parks and Recreation Department or land trust to survey for the cattail flash-train firefly (Photinus consimilis) in as many wetlands as possible.

This helps to determine not just whether a species occurs in your area, but how common it is, how big its population might be, and how it might be responding to threats such as urbanization. Firefly community scientists and professionals have taken this approach with several focal species, but it would be equally worthwhile with Data Deficient species.

Record high-quality observations of the fireflies you find.

Regardless of whether you are in a focal region or whether you have found a focal species, thoroughly documenting the fireflies that you observe will make your data useful and add up to a clearer picture of where different firefly species are found and what sorts of habitats they are persisting in.

In order for a firefly observation to be confidently identified to species, the following is usually necessary (full surveys will require further information):

Geography will guide you, but it shouldn’t be a barrier!

Whether you live in Montana or Manitoba, Missouri or Maine, or any other area outside of the Firefly Atlas focal regions, your surveys and observations can make a meaningful difference for firefly conservation at the local and national scale. Even if you live in California or the Pacific Northwest, where the fireflies are non-flashing, day-active species or glow-worms, there is a need for more data. Getting to know the firefly species in your corner of the world helps bring attention and awareness to the places they depend on, and putting points on a range-wide distribution map gives us a clearer picture of how species are doing.

Now that the adult firefly season has ended for most species in most places, it’s a great time to begin planning your surveys for 2025. If you have lingering questions about how to direct your Firefly Atlas survey efforts, please reach out to us at [email protected].

Notice: Below is a list of 9 important links included on this page.

3. Community Science Code of Conduct

5. Carried out extinction risk assessments for the majority of North American firefly species

7. Available field guides, keys, and identification resources

9. Firefly sanctuary at the Coler Mountain Bike Preserve

Please note that while screen readers have made significant strides, they may still lack full support for optimal web accessibility.

By Richard Joyce, Endangered Species Conservation Biologist

You’ve created a Firefly Atlas account, looked over the participant handbook, and watched the training video. You’ve read the Community Science Code of Conduct, gathered the equipment you’ll need, and printed out survey data-sheets. There’s just one issue: you don’t live in any of the focal regions highlighted on the map below.

The regions on this map correspond to areas with potential habitat for firefly species that are of particular concern for conservation in the United States, so Firefly Atlas participation in these regions is particularly valuable. However, firefly surveys from all across the USA and Canada are meaningful contributions to firefly conservation. Your geographic location will influence how you contribute to the Firefly Atlas, but it should not determine whether you participate.

In this blog post, I’ll explain how to direct your firefly survey efforts for the greatest contribution to firefly conservation, even if you live outside of a focal survey region.

Figure out which Data Deficient species could be in your area and then search for them.

Back in 2021 when the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Firefly Specialist Group carried out extinction risk assessments for the majority of North American firefly species, it was revealed that over half of the assessed species lacked the necessary information to determine their conservation status. In other words, these species could be doing fine (Red List Least Concern) or they could be in trouble (Red List Endangered), but we simply don’t know enough about their current distribution or population levels. The technical term for this category is “Data Deficient” (DD).

Using the Firefly Species Checklist, you can to filter species that have a Red List category of “DD” and are found in your state or province or in neighboring states and provinces.

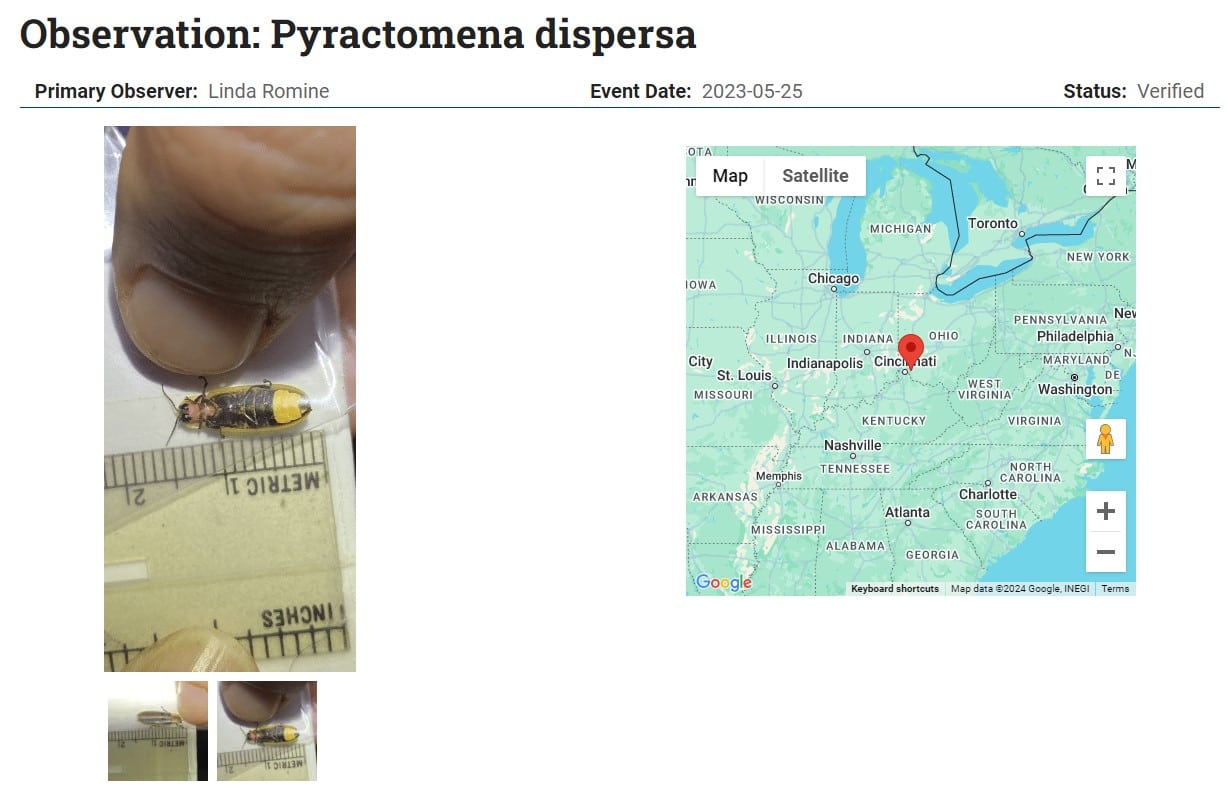

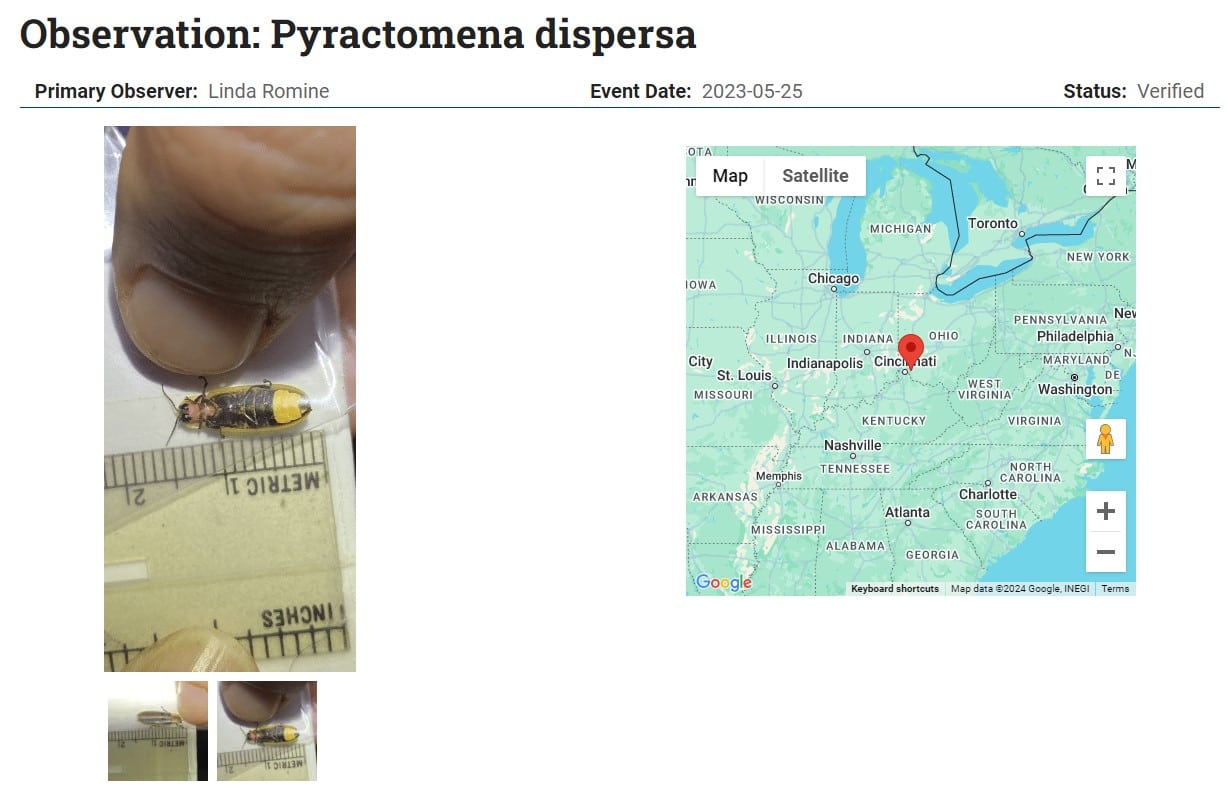

Here are some of the Data Deficient species for which Firefly Atlas participants have surveyed so far:

- Cattail flash-train firefly (Photinus consimilis) in North Carolina

- Thinly girdled firefly (Photinus tenuicinctus) in Arkansas

- Marsh imp (Pyractomena lucifera) in Texas

- Similar firefly (Pyractomena similis) in Virginia

- Prairie train firefly (Photuris missouriensis) in Colorado and New Mexico

- Marsh flicker (Pyractomena dispersa) in Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Ohio, Nevada, and North Carolina

- Northern ablaze flash-train firefly (Photinus ardens) in Ontario

Once you’ve created a list of Data Deficient species that might be in your area, you can learn more about each of these species on their Red List pages, as well as in the available field guides, keys, and identification resources. These sources will help guide you on what time of year to survey, what flash patterns or other behavior to look for, and what habitats to survey in.

Do a full inventory of firefly species for your local park or green space.

Another approach is to begin creating a full species list for whatever green space you have access to, whether that is your backyard or a local park or nature center. You can begin by documenting the most common species, and as you spend more time surveying for fireflies, you will likely start to notice fireflies that are less common.

Across North America, volunteer naturalists are making illuminating discoveries as they gradually create lists of the fireflies found in their local green spaces. For example, the “Glow Patrol Firefly Research Team” has successfully documented seven species at Armand Bayou Nature Center in Pasadena, Texas, and the volunteers at the firefly sanctuary at the Coler Mountain Bike Preserve in Bentonville, Arkansas are also inventorying their lightning bugs.

Survey lots of sites for one species

Once you’ve found a given species and know that its display season has begun, you can explore the question of how widespread it is in your community. For example, you might collaborate with your local Parks and Recreation Department or land trust to survey for the cattail flash-train firefly (Photinus consimilis) in as many wetlands as possible.

This helps to determine not just whether a species occurs in your area, but how common it is, how big its population might be, and how it might be responding to threats such as urbanization. Firefly community scientists and professionals have taken this approach with several focal species, but it would be equally worthwhile with Data Deficient species.

Record high-quality observations of the fireflies you find.

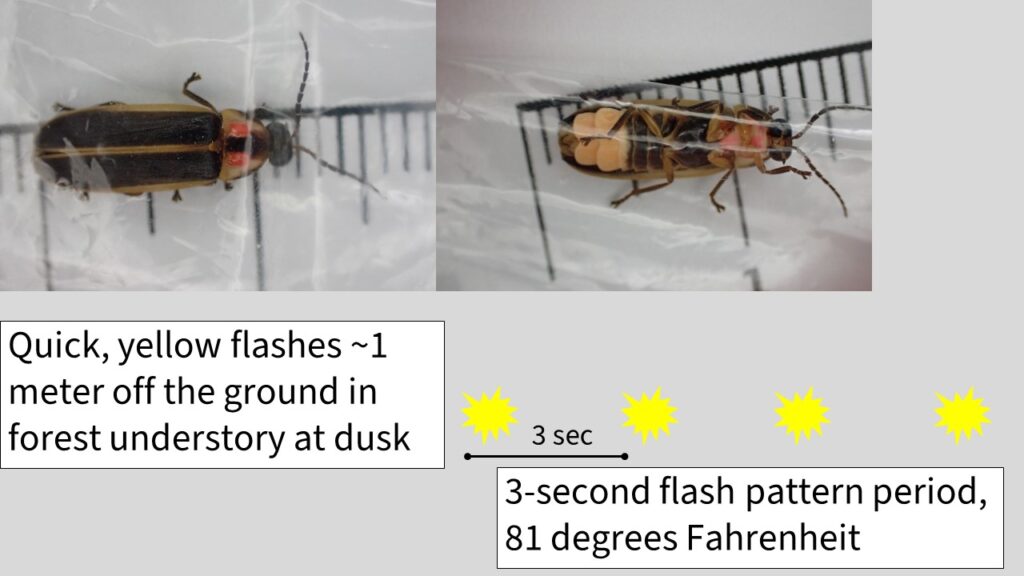

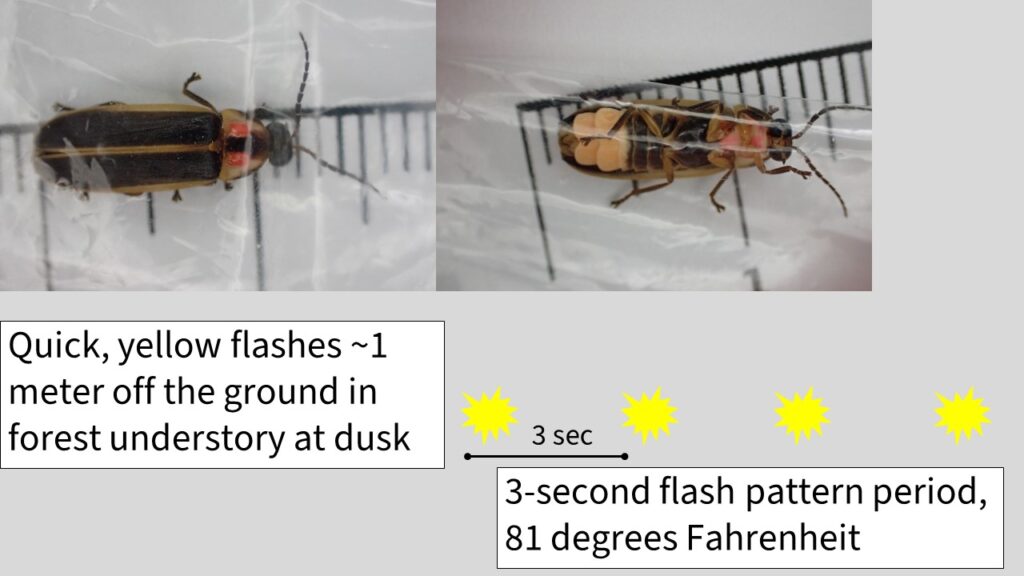

Regardless of whether you are in a focal region or whether you have found a focal species, thoroughly documenting the fireflies that you observe will make your data useful and add up to a clearer picture of where different firefly species are found and what sorts of habitats they are persisting in.

In order for a firefly observation to be confidently identified to species, the following is usually necessary (full surveys will require further information):

- A close-up photo of the firefly’s upperside (“back”)

- A close-up photo of the firefly’s underside (“belly”)

- Flash pattern details, including the air temperature at the time of flashing (for flashing firefly species)

- Notes on where the firefly was within the habitat

Geography will guide you, but it shouldn’t be a barrier!

Whether you live in Montana or Manitoba, Missouri or Maine, or any other area outside of the Firefly Atlas focal regions, your surveys and observations can make a meaningful difference for firefly conservation at the local and national scale. Even if you live in California or the Pacific Northwest, where the fireflies are non-flashing, day-active species or glow-worms, there is a need for more data. Getting to know the firefly species in your corner of the world helps bring attention and awareness to the places they depend on, and putting points on a range-wide distribution map gives us a clearer picture of how species are doing.

Now that the adult firefly season has ended for most species in most places, it’s a great time to begin planning your surveys for 2025. If you have lingering questions about how to direct your Firefly Atlas survey efforts, please reach out to us at [email protected].